| |

PDF Version |

|

By Dave Ream July 2008 Honeymoon Letter

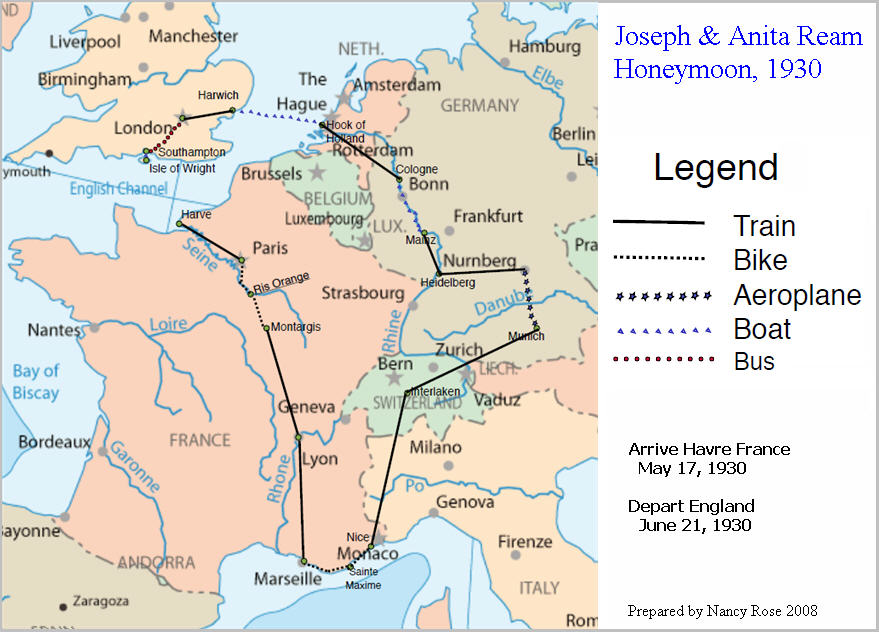

1930--Introduction In May and June of 1930, my parents, Joe Ream and Anita

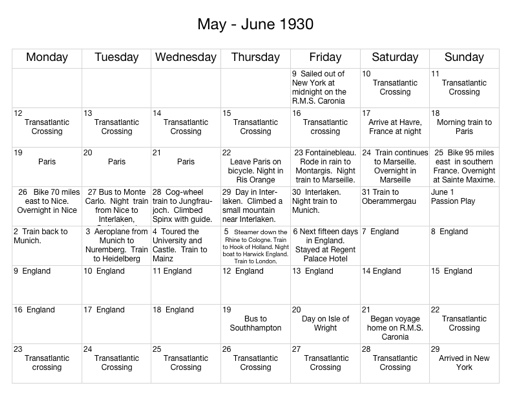

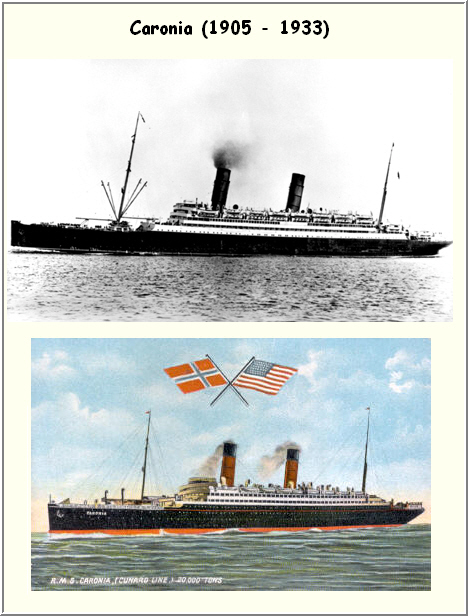

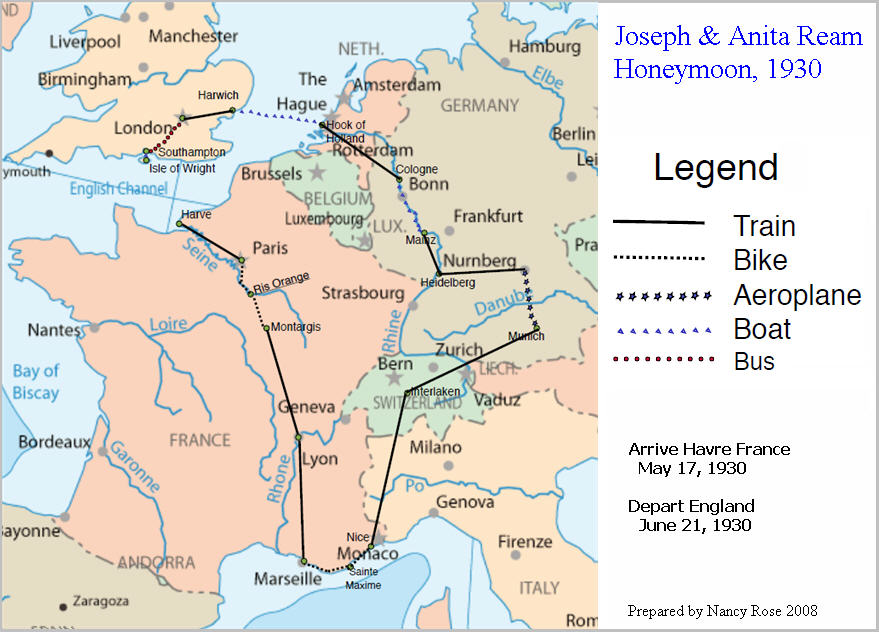

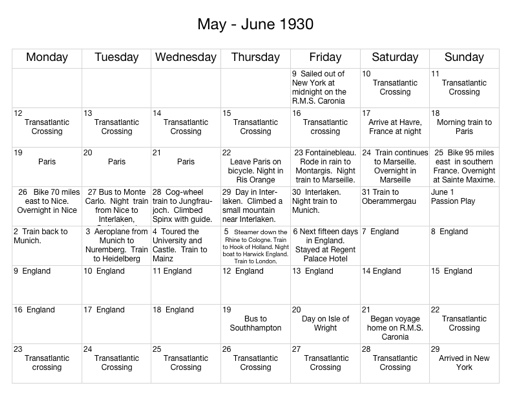

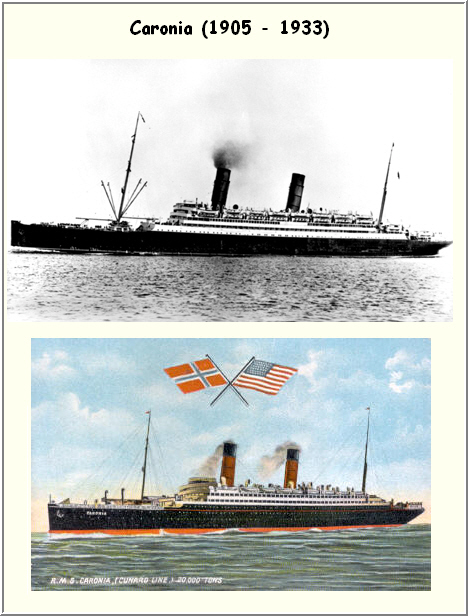

Biggs, traveled to Joe was 26 years old, Anita was 23, they were in excellent health, both had completed their higher education, and the European tour was looked upon as sort of a last fling before they settled down to start a family, and for Joe to pursue his legal career. Joe Ream, known more familiarly in later years by his descendants as the Old Man, wrote a chronicle of their European trip. He took the time to write it on board the Caronia on their homeward bound sailing; that chronicle has been dubbed “Honeymoon Letter 1930,” and it follows immediately after this background information. I believe that he wrote it in longhand, then had someone at his law firm type it up and make carbon copies. These were distributed to his and Anita’s families; that is why it is addressed to “my dear family,” and why the author is occasionally “talking to” the reader. In 2008, Nancy Rose was able to obtain a faded carbon copy of the chronicle. She retyped it so that it could be read more easily, and John Ream has posted it on the Ream family home page for all to read, along with some black-and-white photos of the trip (poor quality for such old photos). Here’s a bit more background. Both of our parents came from humble but

respectable backgrounds. Each was a

child of Protestant clergymen who served primarily in the Midwest—small towns

and cities in Meanwhile, Anita and her sister Portia were teaching school

for a year or two in rural Joe and Anita met through a mutual friend from The demands of Joe’s work at the Cravath firm were heavy,

one result being that the newly-weds had no time for a proper honeymoon (beyond

a couple of nights in I won’t bother to recount their day-to-day activities on the

Caronia and in European cities and countryside.

The chronicle, along with A couple of observations. There was much more formality to life back in 1930, as evidenced by the words and photos of the honeymoon chronicle. Men wore coat-and-tie most of the time. Women wore dresses or skirts. No blue jeans, no shorts, no sandals or flip-flops, etc. One “dressed for dinner” on board the ship (black tie?). My parents had a healthy respect for Christian belief,

certainly more than my own attitude on the subject of religion. The even stronger faith of their parents,

whose lives revolved around their church, rubbed off on them. Cassie Ream, the Old Man’s mother, was a

particularly strong believer and supporter of Christian missionary

activities. With this background, it is

not surprising that in the chronicle the Old Man devotes a lot of space

describing the Passion Play at The religion aspect also had an effect on their attitudes

toward drinking alcoholic beverages.

They were both raised by Protestant ministers who were strict

teetotalers. Recall also that national

prohibition was still in effect in the On returning to They were in Their favorable experiences in the two separate trips to At the end of 1931, Joe and Anita discovered that she was

pregnant. She returned to A look back at This Introduction was written in 2008 by Dave Ream (third

son of Joe and Anita Ream), with input from Nancy Rose (daughter of Joe and

Anita), Jack Ream (first son), Chris Ream (fourth son), and Holly Noble (only

child of Walter and Portia Hahn). |

|

On Board R. M. S. Caronia June 21, 1930 My dear Family, My contribution to the family letter this time is going to be a more or

less detailed chronicle of our trip to Europe.

Now that we are homeward bound on board the same boat that took us

eastward, I intend to use some of my leisure time in composing this letter,

realizing that it would be difficult to find the time to do so after we reach

New York. When we planned our trip to Europe we did so by making no

plans at all. We did have one or two

pretty well-defined ideas of how it should be done, however. First, we intended to do only what we wanted

to do and to see only those things that attracted us. In other words, we didn’t go to Europe with

the idea of acquiring an education but solely with the idea of having a good

time. Hence we are coming away with

practically no idea at all of most places of interest to the ordinary run of

tourists. Second, we intended, in so far

as possible, to speak the language, eat the food, drink the beverages, and in

short to live the life of the people of the country in which we found

ourselves. This entailed, of course, a

divergence from the beaten path of travel, and we studiously avoided anything

that had to do with tourist parties. After

these preliminary remarks, we had better be getting on with the chronicle

itself. We sailed out of New York at midnight on the 9th of May under most

propitious conditions. We had packed our

three small bags in a half hour, after a leisurely dinner, and nonchalantly

went on board about 10 o’clock. (We did

not forget a single thing that we wanted.)

A large group of friends were down to see us off, and we felt indeed

like a couple of honeymooners. The night

was hot, the moon almost full, and you can imagine the thrill it gave us to see

the familiar lights of lower Manhattan move slowly by and finally fade away and

to realize that we were actually on our way and had irrevocably cut ourselves

off for many weeks to come from everything that we had known. The Caronia is a cabin boat of about 20,000 tons, which means that it is

fairly small and fairly slow as compared with the bigger ocean liners and that

we had the run of the boat and could go any place we pleased. I strongly recommend this type of boat for

one making the trip for the first time at least, as we found the voyage one of

the most enjoyable parts of the whole trip.

While there is really nothing in the world to do on board ship it is

astonishing how quickly and pleasantly the time passes. You soon know about half of the passengers

(there are always some, of course, whom you never meet) and everyone has no

more to do in the next seven or eight days than you have and is as ready for

any sort of entertainment or just ordinary loafing as you are. Here is a typical day-- Up for breakfast about nine o’clock (you should see the menus on these

ships, and you can eat any or all of it--that is if your tummy can expand

sufficiently.) Then a few turns about

the deck and perhaps an hour or so of shuffle-board, deck tennis, deck hockey, or other games.

About this time along comes the deck steward with some hot bouillon and

wafers and you sit down in your deck chair to take a little nourishment after your exertions. By that time you probably decide you are

exhausted so you loll back in your deck chair (by the way, the most comfortable

chairs every invented) and sun yourself while waiting for the call to lunch. At lunch you can, if you are foolish enough,

eat enough to satisfy a couple of section hands, but by the second day you have

learned that just because the food is free is no reason for eating everything

on the menu. Then, after lunch perhaps some more turns about the deck, another deck game or so, a little reading in your deck

chair, and perhaps some bridge in one of the lounges. About four o’clock this is broken up by some

tea and cakes, and soon it is time to dress for dinner. After dinner there is opportunity for a bit

of dancing (which, however, is quite difficult if the boat begins to rock too

much) and after a little congenial conversation with your traveling companions

it is time for bed. We met several very interesting persons on board--some who were regular

globe-trotters--but I can’t bore you with describing them in this letter. On Saturday night, after eight days, we got to Havre, but

did not land until the following morning.

There we got our first opportunity--and necessity--of speaking

French. A special train took us to Paris. Rather unexpectedly

and very fortunately for us, as we had no idea as to where we would stay or

anything of that nature, we were met by Herve Pleven, a French friend of ours who had spent several months in the

office in New York. He took charge of us

and fixed us up in a nice little hotel.

We spent Sunday afternoon wandering about the city, afoot and in the

frightfully cheap taxis. We saw the

Gardens of the Tuileries, which adjoins

the Louvre, and the statue of Lafayette there; the statue was erected by American school children. One of the big fountains in the Gardens--the

size of a small pond--was covered with toy sail boats which French children

were sailing. We then wandered up the

Champs Elysees Avenue and saw the Arc of Triumph, erected to commemorate the victories of Napoleon. On the pavement in the

center of the Arc is the grave of the unknown French soldier who died in the

War, and at the head of the grave burns the so-called “perpetual fire.” I understand that this fire is extinguished for five

minutes every day at three o’clock and then relit, amid appropriate ceremonies,

by some patriotic organization. We then

drove out through the Bois de Boulogne, a great park which borders the city of

the northwest, and had tea there. We spent only four

days in Paris, and much of the time we simply wandered about the streets,

trying to speak French and to learn how the people lived. We did, however, take in three other

“sights”--the Palace of the Louvre, the Cathedral of Notre Dame, and Napoleon’s tomb. The Louvre, as you know, used to be the palace of the

kings.

While not more than three and four stories high, it covers a great deal of ground. Today it has the greatest collection of

paintings and sculpture in the world. It gave us no

little thrill to see the originals of the famous pieces with which we were

familiar through the many copies which we have seen. The two most famous pieces are, of course,

the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci and the Venus de Milo. Throughout all the galleries of paintings

were artists with their easels and palettes making copies of the originals on

the walls, and of course, there was a fellow with longish hair making a copy of

the Mona Lisa. However, his copy, like

all the rest that I have seen--and I know nothing about art--was a pretty poor

imitation of the original, as he was getting the face too long and narrow and

the expression on the face ultra-enigmatic.

In the original the face and forehead are quite broad and the whole

expression kindly rather than seductive and enigmatic. The Venus de Milo has a whole room to herself

and is wonderful, but I could tell no differences between the original and the

copies except that the original is quite stained and the marble is eaten away

in several places. Herve told us that

hundreds of sculptors have tried to construct arms for the figure, but that no

matter in what position they were placed the addition of the arms spoiled the

perfect symmetry of the whole, so that they have to come to believe that the

statue never did have arms. I suppose Notre Dame is the most famous cathedral in the world on account

of the hundreds of years it took to build and the many historic events

connected with it. It has an air of great

antiquity about it, its white stone

having been turned to black in most places by the soot and the dirt of

centuries. We climbed up to the top and

stood beside the famous gargoyles which typify the evil spirits, and I am sorry

that we did not have our camera along so that I could take a picture of Anita

standing beside that jolly old fellow with his tongue sticking out. While we

were in the cathedral several groups of little children escorted by monks came

through, the monks explaining, I suppose, the various parts of the cathedral to

them. While the Roman Catholic is about

the only religion of importance in France, I understand that the younger

generation of Frenchman pay very little attention to religion as a rule. Napoleon’s tomb is a typical sight for tourists, so we

didn’t enjoy it very much, and I won’t trouble you with it or the adjacent

military museum. The restaurants and side-walk cafes in Paris and

throughout France were a constant satisfaction.

The French are undoubtedly the best cooks in the world, and I believe

that eating is about the most important thing in life to the average

Frenchman. Except for breakfast, which

throughout continental Europe which we visited consists of rolls and butter and

very strong coffee and nothing more, the meals are huge. The French food is very rich and quite oily

and greasy. For this reason and because

they say that the water is not fit to drink, the French have wine at every

meal. The water may not be good, but it

certainly will not kill, as we drank a large amount of it with no ill

effects. I seldom saw any drinking

except at meals, and I don’t believe Frenchman drink at other times except very

moderately. Wine may be had at any

price, but ordinary table wine costs from 5 to 20 francs (20 cents to 80 cents)

a bottle, and I believe one would have to drink a gallon or more to become

intoxicated. It does cut the oily, heavy

taste of the food, and I suppose it is essential if one is really to enjoy the

food, although I must admit that our taste was not sufficiently cultivated to

enjoy the wine by itself. Wednesday we did some shopping and while we were wandering through one of

the big department stores--Au Printemps--we saw a good collection of bicycles

on display. Bicycling in Europe is a

universal means of travel, the streets and roads are full of them, and it is no

uncommon sight to see a woman riding along carrying a child in a basket in

front of her. I forgot to tell you that

ever since we arrived in Paris, the change from the bracing sea air afflicted

us with extreme lassitude and drowsiness, and the more we rested and slept the

more tired and sleepy we became. We

simply could not stay up at night at all, so that we missed out entirely on

Paris night life. We were in a state of

mind where something had to be done when we saw these bicycles in the store,

and they gave us the brilliant idea to buy a tandem and ride about the country

on it. We had a little difficulty in finding a tandem, but finally we did find

one which was a beauty--three speeds, three brakes, balloon tires, etc. We bought it for 1700 francs or about

$68. We then packed one of our three

bags with things that we would not need and left it with the steamship company

for forwarding to the boat, and strapping our other two bags on the bicycle,

one in front and one behind, we started our trip about eleven o’clock on

Thursday morning. Our immediate destination was Versailles, the summer palace of the kings,

about 15 miles southwest of Paris. It

was with little regret that we left Paris behind us and started out through the

beautiful country. The heavy bag in

front made guiding and balancing a little difficult until we got the hang of

it. The chain slipped off on one tumble

and we wasted quite a lot of time before we got it adjusted again. Stopping to eat along the road, we arrived in

Versailles about three o’clock and rode through the beautiful grounds and went

through the palace. Our next point was Fontainebleau, about 45 miles

southeast of Versailles. The first part

of this jump was through pretty country, but for the most part the country was

largely agricultural and a little industrial.

We stopped that night, completely worn out from our first day on the

bicycle at a little inn near a tiny town called Ris Orangis. We slept like logs that evening and were up

at the crack of dawn, but as stiff as boards.

We had not been on the road

long until it started to rain and this soon developed into a downpour. As we had no raincoats, we got pretty wet and

soon stopped for breakfast. The rain let

up a bit after a while but settled down to what looked like an all day

proposition. We were wet and cold and

ached in every joint as we sat there at the breakfast table, but decided that

the only thing to do was to go on, rain or no rain. We went right ahead then, through the rain

all the time, getting wetter and wetter, with our clothes weighing tons, but we

kept ourselves warm through exercise and arrived in Fontainebleau about eleven o’clock. We went to a

little pension--which is a combination small hotel and boarding house--took hot

baths, had lunch and loafed around our room while our clothes were drying out

in the kitchen, About four o’clock the rain stopped

and the sun came out; this raised our spirits

about 1000%. We were quite rested and

decided that the thing to do was to start on again as our clothes were

practically dry. The little town of Fontainebleau is

completely surrounded by the Forest of Fontainebleau, and it was great sport

riding through it after the rain. We headed south. After we got out of

the forest we struck some very pretty small-farming country, following all the

way an old canal called the Canal du Loing.

We unanimously agreed that here surely

was the life! We decided to try to reach Montargis, a

fair-sized town about 30 miles south of Fontainebleau before dark, as we wanted

to take the train to Marseilles. We were

sailing along until about 7:30 when it started to rain again, with us still

about twelve miles from Montargis. As we

were getting pretty ravenous and didn’t care about getting soaked again we

stopped at a tiny little store near Suppes run by an old woman. We bought some bread and cheese and sardines and

washed these down with a bottle of wine.

I really believe that we enjoyed this little

meal more than any we had during our whole trip. We did not leave a crumb. We were just finishing when the old woman

shouted “Le soleil.” I dashed to the door and sure enough the rain

had stopped and the sun was shining. We

hopped on the bicycle and as it was getting late we pedaled as hard as we could

to get to

Montargis as soon as possible. We reached the edge of Montargis just as it

got dark and started to rain again, but fortunately the station was close and we

only got a little damp. We had a difficult enough time getting our tickets to

Marseilles and shipping the bicycle. The ticket agent told us that

we would not reach Marseilles until

midnight of the following night, but as a matter of fact we

did get there about four o’clock in the afternoon, that being our first taste

of the mistake of placing reliance on anything you were told about train

schedules. After fortifying ourselves with several cups of hot

chocolate, we got on the train about eleven o’clock, and after one o’clock found

ourselves alone in our second-class compartment. The European coaches are all divided into

compartments each with its separate door and are similar to a Pullman

compartment except that there are no sleeping accommodations and the seats are

much longer. As soon as we were alone,

we each stretched out on a seat and slept pretty well until we got to Lyon

about seven o’clock in the morning.

After breakfast there and waiting awhile for our train, we got on a very

good express and were able to get lunch on the train. You have to go into the dining car at a

particular time, and then the waiters serve everyone the same thing at the same

time. There is no choice as to what you

will eat, but as I recall it was a very good meal. Marseilles is

quite a shipping port and I think it the dirtiest and ugliest city that we

saw. The hotel that we stopped at was a

horrible affair, but we were out bright and early the following morning

(Sunday) and so did not mind it much. About ten miles out of Marseilles we saw a bicycle race participated in by at least 200

men and boys. They whizzed by us on the

road in groups of twenty or so, all with bright colored sweaters, but we knew

nothing about the outcome. It was along this road also, on a hill, that we saw

our trolley bus, which looked just like a regular motor bus except that the

power came from overhead electric wires through trolley poles. I don’t know what would happen to it if the

driver ever made a wrong turn and the trolley poles got out of reach of the

wires.

When we left

Marseilles we planned to go to Nice which is also on the

Mediterranean about 160 miles east of Marseilles. We had sent our two bags by train

to Nice, keeping only a few necessary articles in a small satchel, so as to

lighten the load on the bicycle.

Although the road did not skirt the sea until the last 70 miles, we had

looked forward to fairly flat

country as hills were difficult even in low gear. In this, however, we were disappointed, as it

was hilly most of the way. The country

was almost tropical in appearance, although we did not see many palms until we

got near Nice. There was very little

farming except for vineyards and one mammoth hill, called Col de l’Ange, on which were orchards of olive

trees. We got a lift most of the way up

this hill by holding onto a big truck which itself was having difficulty in

getting up. After we got to the top we

were able to coast about ten miles down this hill, winding back and forth and

forced to use the brakes much of the time.

For real sport we have agreed that nothing can touch coasting down long

hills on a tandem once you have been able to get to the top. Although Anita did not like going too fast

down hills that we did not know, it always struck her as positively unjust that

we had to retard our progress by braking on a hill that we had climbed with

such difficulty.

We had lunch that

day in Toulon which is a good sized

town with several resort hotels. About

15 miles out of Toulon we struck wooded country again and it was very

pretty. It was in here that we met the

two gendarmes. We were coasting down a

hill, and we were a somewhat unusual sight, when we passed these two policemen leaning

against a culvert. As we had seen

several soldiers along the road that day I scarcely noticed them, but

apparently they spoke or waved to us. We

had just passed merrily by when we heard the universal police whistle and here

they were coming for us. When we had

shipped the bicycle on the train someone had stolen our bell and one of our

little license plaques and apparently it was quite serious to travel without

them. They examined our passport and put

us through a long set of questions, but eventually became very amused at our efforts to speak French and let us go

with warnings about the steep hill which awaited us. This hill, Col de Grattaloup, was over three

miles long and very steep so that we had to walk all the way. It was beautiful country, however. After

refreshments at a little inn just over the top we followed the road, down-hill

or level, all the way for over 15 miles to the sea. The country was pretty farming land, and we

were in the best of spirits. We then

followed the seashore around the Gulf of Saint Tropez, which is a little arm of

the Mediterranean, to Sainte Maxime where we stopped at the most delightful

place of the whole trip. It was a tiny,

little pension built out over the rocks, and the French windows of our room

opened out on a little veranda where the waves almost splashed in our

faces. We went to sleep that night to

the music of the sea, dead tired after our 95 miles on the bicycle.

The trip that day

had been under a good hot sun all the way, and Anita, having worn a sleeveless

blouse, had as nice a case of sunburn on the arms and shoulders as I have

seen. It was over a week until certain

spots ceased to be sore to the touch. The following day we followed the sea all the way to

Nice, about seventy miles, but our hopes of a level road were doomed, as the

foothills of the Alps come right down to the sea, and the road was going

constantly up and down. The result, however, was the most delightful scenery composed of hills and

sea, alternate rocky and sandy shores, and a glorious sun shining over us. All along also were resort hotels and magnificent

estates with beautiful grounds set out with lovely palms. Shortly after noon we got to Cannes, which I

suppose is one of the three most popular resort spots for people who have

oodles of money and lots of time to spend it. We went on toward Nice, but about

eight miles out we had a puncture and it started to rain so we got on a train

and arrived in Nice about five o’clock, quite travelworn and very dirty. As we had no further use for the

bicycle and could only get 500 francs for it in Nice, we shipped it back to

Paris to be sold, but have not heard from it as yet.

Nice was the

cleanest and most modern of the French cities that we saw, and while it might

be very nice to live there it was too much like our American cities for us to

enthuse over it as we were interested in things that were different. The next day we went out on a bus to Monte Carlo which is

the capital and only city of Monaco, an independent little state only a few

square miles in area. The casino here is

the most famous gambling den in the world, and we were anxious to see what it

was all about. The casino is a large

magnificent building and the gambling rooms themselves have ceilings about four

stories high and are more luxurious than the hall of the kings in the

Louvre. There were hundreds of attendants

about, in full dress, standing stiffly at attention or watching the players at

the roulette tables, and scores of others in scarlet, with knee breeches and

silk stockings, just merely standing.

Everything was perfectly quiet and as dignified as a church, and I

believe that Anita and I were the only ones who ever smiled. We wanted to take a fling at it and

eventually found an attendant who could explain the game to us in English. We only had an hour to play, but that was

long enough for us to lose 600 francs, or

nearly $24. As this was Wednesday we hurried back to Nice, because we

wanted to get to Switzerland for a day or so and then to the Passion Play on

Sunday. We had some laundry done at Nice. Anita had sent her

coat to be cleaned, having been promised it by that afternoon. We got the laundry all right but shall never

see the coat again. Our trip through France was, I think, in many ways the

most satisfying of the whole trip. We

were completely off the beaten track, got an excellent eye-to-eye view of the

country and the people, and were forced to speak French practically all the

time. Needless to say, we soon got so

that we were able to express ourselves sufficiently well to get anything that

we wanted. It used to make us mad when some Frenchman who knew a few

words of English would try to speak English to us instead of French. It

was with real regret that we said good-bye to la belle France and the good old

“bicyclette.” We took the night train of the International Express to

Switzerland late that afternoon and passed through Italy where we submitted to

customs examination, but that is all we saw of Italy. We were at

Interlaken the following morning. It was

frightfully cold, but one of the few things we had wanted to do in Europe was

to climb the Jungfrau, which is one of

the three highest peaks in the Alps and perpetually covered with snow and ice. That morning, we took the cog-wheel electric railway up

to Jungfraujoch, which is a little ridge about 2000 feet below the peak of the

Jungfrau. The mountain scenery along the

way is the best I have ever seen and while similar to the Rockies in many ways,

there is a bleakness and grandeur--and even an intimacy--about these Alpine

peaks that you cannot find in the Rockies.

The last ten or fifteen miles of our track we tunneled right through the

middle of an adjacent peak, and I don’t now recall how many years or how many

millions of francs it took to build this road, but it surely is a wonderful

feat of engineering. It began to snow long before we reached Jungfraujoch, and

by the time we got off at the last stop, we were in the midst of a regular

blizzard. We soon found out that it

would be out of the question to climb the Jungfrau for several days, as recently fallen snow hides the landmarks on the peak

and makes a very insecure footing. We

decided that we would have to give it up as there was not a guide who would

attempt it, and we were finding Switzerland altogether too expensive for a

protracted stay. However, we wanted to

do some climbing, so we hired a guide and some suitable clothes and

paraphernalia (the most important of which were spiked shoes and an alpine

stick) and attempted the Sphinx, a little secondary peak about 1000 feet above

Jungfraujoch, and which had not been climbed yet this year. The three of us tied ourselves together with

ropes and the guide went ahead picking the way.

It was still snowing and the wind was blowing a gale, and we could not

see more than twenty feet at any time.

At one place the guide had to chop little steps out of a wall of ice for

us to place our feet. At another point

we got a thrill that we will not forget in a hurry. The guide would punch his stick through the

snow to find a solid footing of ice underneath, and once near the edge of a

precipice his stick found no ice but went right through the snow. He showed us the hole, and sure enough there

was light at the bottom. The explanation

was that the soft snow had formed a drift on the edge of the precipice, and while it looked as solid as any of the rest, a step on that snow would have plunged one some hundreds

of feet down over the precipice. We got

to the top of the Sphinx all right and back to Jungfraujoch in time to catch

the last train down to Interlaken. At Interlaken, we stayed at the oldest house in the

village--over 300 years old--and as pretty on the outside as any Swiss house we

saw. On the inside the ceilings were

very low and there was a total lack of modern plumbing, but we enjoyed it

nevertheless. The next day we climbed a

small mountain close by which was completely wooded and without snow. That evening we took a bath. At any place in continental Europe a bath is

an event and always costs considerably extra.

This particular bath was more of an event than usual, as of course there

were no facilities in the house, and we had to walk two or three blocks to

where an enterprising Swiss groceryman had fitted up a little bathrooom above

the storage place in the rear of his store.

Ladies first being my motto, Anita had the first crack at it with the

result that there was scarcely enough hot water left to take the first chill

off of my bath, and no chance for more hot water that evening. Thus passed a very pleasant evening for us. The next day, Friday, we took the train for Munich. Although

we missed the first train (it was standing on the track, but we mistook it for

a freight train) and did not get out of Interlaken till late that afternoon, we

got to Munich early the following morning, by riding all night in our second

class compartment. We passed through

Lucerne and Zurich but saw very little of them. A word in parting as to Switzerland. The mountain scenery here is undoubtedly the

best in the world, but it left us pretty cold--both literally and

figuratively--as we gathered the impression that the one and only industry of importance

in the country is the traffic in tourists.

We did think, however, that it would be great sport to take a little

cottage for the summer on the side of a mountain and actually live there for

awhile, but the prospect of dashing madly from one wonderful sight to another

held no appeal for us. We were a little afraid that we would not be able to

secure tickets for the Passion Play as we had made no arrangements before

arriving in Munich. But by refusing to take “No” for an answer at the office

in Munich we were able to get fixed up all right. After buying a coat for Anita to replace the

one left behind at Nice, we took a special train and arrived in Oberammergau

that afternoon and went directly to our room which was at the house of the girl

who played the part of Salome, the friend of Christ. All of the houses in the village were spick

and span, and on the outside walls of many of them were large paintings, mostly

of a religious nature. The majority of

the men, of course, had beards and long hair for the occasion, and most of them

wore the typical Bavarian costume, the chief part of which is the short leather

or canvas breeches held up by leather suspenders. The village was simply thronged with tourists,

mostly Americans it seemed to us, and nearly every house in the village, except

those in the outskirts, had one or two rooms on the ground floor turned into a

shop for curios and souvenirs. The

commercialized aspect of the whole place gave us a bit of a shock that first

evening. This

year for the first time the audience at the Passion Play has sat under a

roof. The theatre is an unusual sort of

building with the stage itself under the open sky with a view of the hills

beyond, and when the sun shines down upon the stage it is truly a beautiful

sight. Some of you know a great deal more than I

do about the facts and figures of the Passion Play, so I won’t bore you with a

recital of these. I had thought that the

play covered more of the life of Christ than the last week, but aside from the

tableaux (of which more later) the whole of the nearly eight hours of the

performance were taken up with the last week, the crucifixion, and resurrection.

All of the speaking was in German, and although we followed along with

an English translation, I believe that we missed a great deal by not being able

to understand the words as they were actually spoken. The only way to speak of the Passion Play is

in terms of superlatives. It is truly a

wonderful performance, and it should not be missed, although I hardly think it

is worth a trip to Europe to see only that.

In the center of the stage was a little curtained off part, which was

the only place where scenery was shifted, and it was here that the tableaux

were given. At each tableau the choir

sang and Anton Lang spoke a prologue in verse.

Anton Lang is a majestic figure, and I am sure that his portrayal of the

Christ must have been far superior to that of Alois Lang, who by the way is not

a relative. The tableaux represent events

in the Bible, Old Testament for the most part, and for color and perfection of

execution we have never seen anything that could touch them.

Any attempt to appraise the Passion Play is bound to be rather futile,

as it must be influenced largely by the background of the appraiser. As you know the Oberammergaus are Roman

Catholics, and the emphasis which they place on the New Testament is apparently

on the sufferings of Jesus, the perfidy of Judas, and the wicked schemings of the Jewish priests, while I have always

considered these a very minor part of the background of the Christian

religion. The result is that in the

Passion Play the scheming of Judas and the high priests takes up a very large

part of the time, and I believe that Caiphas, the high priest, has more to say

and spends more time in the center of the stage than any other character, not

excepting the Christ. The Passion Play

is, of course, a gigantic spectacle with the hundreds of actors on the stage at

the same time, and you all know that our background in religion has rather been

one of simplicity. The result was that

the Passion Play was for us not a deep religious experience, although it

undoubtedly is to a great many persons. The charge has often been made that

the Passion Play is becoming commercialized.

I do not believe this is true as to many of the principal players. For instance, I have no doubt that Anton Lang is above anything of the sort--one look at

his face would dispel any such thought, and to me he typifies the Passion Play

spirit as it should be. To the great

majority of the people in the village, however, the Passion Play is primarily a

source of revenue. The thousands of

tourists, all with money to spend, cannot help but have one result--that most

of the people are able to sell all sorts of things to them at tourist prices,

and all of the villagers have a style of salesmanship which is anything but

shrinking. The fact that Oberammergau is

cleaner, has much better houses, and

more prosperous inhabitants than the average Bavarian village is due solely, in

my opinion, to the Passion Play. We arrived back in Munich about noon

on Monday and spent most of the afternoon wandering about the city and doing a

little shopping. That evening we went to

the Hofbrauhaus, which I think is the most famous beer house in the world. Beer is to the Germans what wine is to the

French--the universal drink. The

Germans, however, do not confine themselves to drinking with their meals, but

seem to enjoy merely sitting and drinking beer alone. At the Hofbrauhaus we each had a stein

holding a little more than a quart of beer and could scarcely finish it as our

tummies fell far short of the German elasticity. I think it would require several steins to

give any feeling of intoxication, and I am sure that the Germans drink beer

because they like the taste of it rather than for intoxication. Munich is a rather beautiful city with wide streets,

plenty of parks, and is much cleaner than most French cities. There are even more bicycles in Germany than

there are in France. The next morning we went to Nuremberg, about a hundred

miles north--by aeroplane. The cost of

travel by aeroplane in Germany is about the same as first-class railroad fare,

and the Germans have the best system of air routes in the world. The route from Munich to Nuremberg was over

the most beautiful farming country, and the perfect little squares and

triangles of the farms below us looked just like a patch-work quilt. We could just make out a man and some sheep

now and then. Apparently the Germans do

not live right on their farms, but in little

villages of fifteen or twenty houses, from which they go out to work in the

fields. We got to Nuremberg in just over

an hour and I must say that air travel seems a great improvement over any other

kind. Our plane was a rather old one

with a cockpit for two pilots and a little cabin for four passengers. The engine made a good deal of noise and a

few air pockets would give us a dip now and then, but the trip was very

comfortable and we enjoyed it immensely.

Nuremberg is, I think, the

oldest city of any size in Germany, and it surely looks the part. We spent three or four hours wandering about

the city along the narrow little streets, and had lunch (consisting of sausages and a glass of beer) at the Bratwurstglockle, a

very old little inn with autographed pictures of famous men of bye-gone days

covering the walls. Distressingly incongruous

as it may seem, at the next table sat a New York Jewess who spent all the time

telling her friend how frightfully difficult it was to get breakfast for four

people on the electric stove in her New York apartment. Leaving Nuremberg by train we arrived in Heidelberg that evening and spent

the following day looking over the university buildings and the castle. The school buildings look just like any

others on the street and were distinguishable only by the absence of curtains

from the windows and now and then the drone of a professor’s voice through an

open window. The college boys all seemed

to wear distinctive caps, for the most part military in appearance, which I

suppose signified different classes or clubs to which they belonged. The castle stands on a high steep hill overlooking the city, and with all

of its rambling buildings, passages, and

courtyards is a mammoth structure. It is

entirely in ruins now, except for a small part which has been restored, but in

the olden days it must have been able to withstand any and all invaders. In one of the cellar rooms is a wine barrel,

the size of an ordinary room, which holds 49,000 gallons. The head man of the castle used to collect

one-tenth of the wine produced by the people in the surrounding country and put

it into this barrel. In the same room is

a statue of the old keeper of the wine cellar, who is said to have drunk from

fifteen to eighteen bottles (quarts) of wine every day. We went to Mainz that evening and the next day took a steamer down the

Rhine to Cologne. The river from Mainz

to Coblenz (which is halfway to Cologne) is very pretty, although not as

beautiful as our fancy had painted it.

The river seemed to be rather narrow, but it is deep all the way so that

there was plenty of traffic. The hills

rise up on either side of the river and are covered for the most part with

terraced vineyards among the rocks, some of the terraces so small that they do

not have more than half a dozen vines.

Nearly every other hill has a castle on its top, so if you want to have

your “castle on the Rhine” you will have plenty to chose from. We arrived in Cologne with just time to catch our train for the boat to

England, so we hurried right by the famous cathedral of Cologne--walking under

its very shadow--with scarcely a second glance. We enjoyed Germany a great deal but would have enjoyed it much more if we

had been able to speak and understand a little German. But this was quite beyond our power as we could scarcely

make out even the peculiar German printed letters. Everything was much cleaner than in France

and seemed more substantially prosperous.

I believe if one could speak a little German and knew something of the

history and culture of the country, he would have the time of his life in Germany. Our train took us through Holland, but as we did not stop and it was

beginning to get dark then, we did not see very much of the country. We took a night boat from the Hook of Holland

to Harwick, England. We had a perfect channel crossing, sleeping all the way

and arriving in London the next morning. The next fifteen days we spent in England.

I hardly know how to tell you about our doings there, but I think I will

be more brief as England is not so different, and this letter is already

assuming sizeable proportions. We stayed in London at the Regent Palace Hotel which is in the center of

town but still quite reasonable. The

traffic in the streets is left-hand instead of right-hand, and we had several

narrow escapes before we learned the proper technique for crossing the

street. It seems that London spreads out

over a good part of southern England as none of the buildings are over eight or

nine stories high and most of them only three or four. The first Sunday we went with Mr. and Mrs. King, fellow passengers on the

Caronia, who lived in London, up the Thames to Windsor where the King has one

of his castles. The grounds were mammoth

and the buildings themselves rambled over several acres. As the King was not there at the time we were

able to go through most of the grounds.

We later had a picnic supper farther up on the bank of the Thames. The next day we went to the horse races at Hurst Park, and as it was a

holiday, the place was thronged. Horse

racing evokes a universal following among all classes in England--from the King

on down to the poorest workman. Of course we visited Westminster Abbey and that was well worth while, as

the tombs, statues and tablets really meant something to us. Mother, the grave of David Livingstone is one

of the most conspicuous in the whole Abbey, right on the floor of the central

nave not 25 feet from the grave of the unknown soldier. Ben Johnson’s grave was marked by a tiny

square stone which merely said, “O Rare Ben Johnson.” One Sunday we went out to Kew Gardens which I believe is the royal botanical

gardens, at least so far as trees are concerned. It was very delightful with great expanses of

rolling lawn and groups of beautiful trees. Hyde Park is to London what Central Park is to New York, but more so. One of its greatest attractions for me is the

corner where the soap-box orators gather.

You can hear fiery words on any subject under the sun (although it is

sometimes difficult to discover just what the speaker is talking about) and the

heckling by the listeners always provokes some lively repartee. Adjoining Hyde Park is Kensington Gardens, the high light of which is the

most charming little statue in the whole world--Peter Pan standing on a little pedestal covered

with rabbits, mice, and fairies. The little kiddies love this and the bronze

mice, rabbits, and fairies are

rubbed shiny by their little hands. The Tower of London, the oldest part of the city, dates back to William the

Conqueror and has a few remains left by the Romans. The most interesting spot was the site where

Henry VIII beheaded several of his wives, including Anne Boleyn, the mother of

Queen Elizabeth. We visited the Law Courts one day and heard parts of two cases in the court

of Kings Bench. It was a great deal like

our own courts, except, of course, for the gowns and wigs worn by counsel and

the judge. I must admit, too, that if

the two judges which we saw are typical, they follow the cases much more

closely than our judges and have a knowledge of the law which is unusual in the

United States. We also spent a couple of hours in the House of Commons listening to the

debate on unemployment, which I guess is dwarfing all other political issues in

England at the moment. Ramsay McDonald

was sitting down on the front bench but we did not hear him speak. Lady Astor, who apparently claims to be the

only perennial champion in the House of rights for women, made a peppery talk

which brought forth a good deal of heckling from the government benches and a

good deal of laughter from all sides,

Her talk had very little substance in it, however, and she was quite

disappointing to me. The attendant said

that we were fortunate to hear her as she was always a good show. We went to two plays and enjoyed both--one a serious study of the life of

working girls in England, and the other a slap-stick comedy. Walking and riding about London on buses occupied a great deal of our time

and we acquire a good working knowledge of many of the places, the names of

which are familiar to you--Trafalgar Square, Pall Mall, Leicester Square,

Buckingham Palace, Piccadilly, Soho, etc. Then one night we went to see some dirt track racing, which is merely

motorcycles racing around a quarter mile dirt track. This sport has taken a great hold in London

the last two or three years, there being eight or ten regular tracks with paid riders

attached to each one. They go so fast

that they simply slide around the curves and now and then they take some rather

nasty spills. It was an evening of

continual thrills all right. We ran into a man named Clarke whom I had played bridge with on the boat,

and our last Saturday afternoon in London he took us in his car for a ride

through the country. We were able to get

off the main roads which are traveled by the buses and to get a taste of real

old English countryside which is positively charming. We visited the Stoke Poges church where Gray

penned his famous lines. We stopped for

a late dinner at the Hotel de Paris on the bank of the Thames. Clarke was very fond of it because the last

time he was there two or three years before, the Prince of Wales had dropped in

for some dancing, and it really was a charming place set among delightful

grounds. We stayed on till midnight and

danced, and that constituted the one and only taste of anything resembling

night life that we had on the whole trip. The second day of the Ascot race meeting, we went to the races again. Ascot is the most fashionable race meeting in

England, and royalty always attends. It

is called Royal Ascot because the track itself is on land owned by the

King. We rode a bus which took us right onto the field, and we had expected to see the

King and Queen arrive in state. The day

started with a little rain, however, and after the second race the heavens

opened and it came down in torrents. We

were able to keep comparatively dry in the bus, but the thousands of poor souls who had no shelter were soaked to the

skin. All the pretty frocks and hats

were simply ruined, and as the track was a lake it was necessary to call off

the rest of the race--the first time in history. A bookmaker near the grand-stand was killed

by lightning, but we did not find this out till later. The King and Queen were there, having arrived

by motor, but we did not see them. I almost forgot to tell you that we were able to save enough money out of

the amount we thought we would require in Europe so that I was able to get a

couple of suits and half a dozen shirts in London. Our last night in London we had dinner at the Kings’ home, and this was our

only meal in a private house which we had in Europe (except in Oberammergau

which, of course, we paid for). It was

very pleasant to sit before the open fire and enjoy an evening with congenial

friends once again. The next day we took a bus to Southampton and enjoyed the trip

immensely. The country was quite pretty

for the most part, and it was on this trip that we saw our first thatched

roofs--and these, in my opinion, would make almost any house look

charming. Southampton is a shipping port

and about one-third of the stores are saloons.

That night we saw a sailor drunk on the street, and he is the only drunk

person that we saw in our European travel. The next day we went over to the Isle of Wight where the King has another

of his castles--I think this is the one where he spends the month of August

during the boat racing season. The

industries of the island apparently are boat building, fishing, and traffic in tourists.

We took a bus around the southern part of the island and it is truly a

beautiful spot on the face of earth, but we succeeded in running into rain

again and some fog also, so we could not see as much as we would have liked. The following day was Saturday, the 21st of June--the day we sailed for

home and the day I started this letter. To be consistent I should try to appraise England for you, but I find it

exceedingly difficult. Perhaps a few

unconnected generalities will suffice.

In the first place an Englishman is exceedingly proud of the past and

the traditions of England. Any sort of a

proposed change--even the widening of a road--brings forth a storm of

protest. In the second place there is a

rigid distinction between a man who is a gentleman and a man who is not a

gentleman. I suppose I would be a

gentleman because I am a college man and a lawyer, and perhaps the rest of you

would be gentlemen too. This distinction

exists and so far as I know very few men who are not “gentlemen” are greatly

perturbed by the fact. Thirdly, every

Englishman is in his heart a sportsman, and every type of sport has a huge

following. It would be great to live in

England if one had lots of money, but I am afraid that having to work would

interfere too much with other essentials. ------------------------- It is now Sunday, the 29th of June, and in a few hours we will be

home. I hope this letter has not bored

you too much, as it was quite difficult to make it brief, and even now I’m sure

I could write on and on. I’ll have this copied when I get back to

the office so you can make it out, and if the pictures we took turn out at all

well, I’ll attach some of them. Lots of love to you all, (No Signature) |